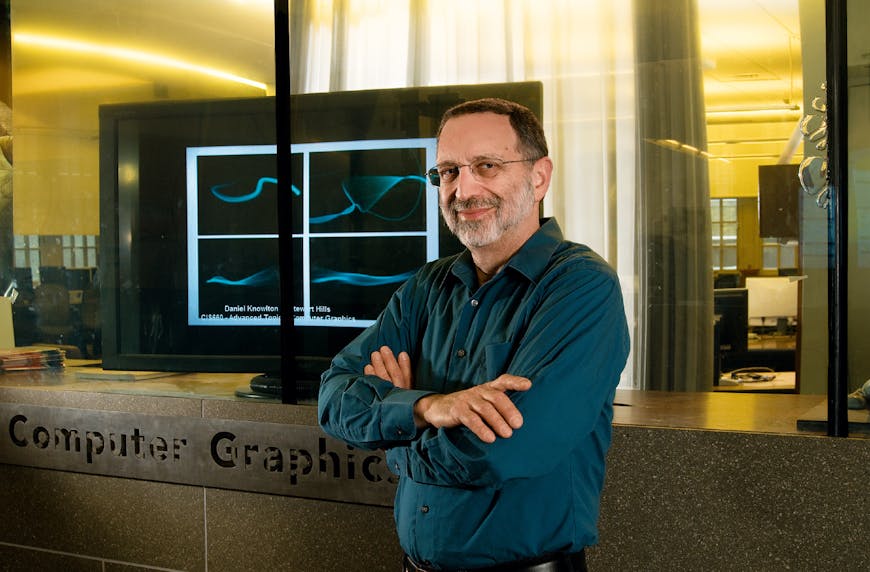

Cesium Welcomes Dr. Norm Badler, Computer Graphics Pioneer, to Head Metaverse Research

I’m extremely honored to welcome Dr. Norm Badler to Cesium to lead Metaverse Research as we make long-term bets on the open metaverse and the role that 3D geospatial plays in bridging our physical and digital worlds.

Professor Badler may appear new to the Cesium community but he has been behind the scenes since well before our start. Without him, there would be no Cesium.

Professor Badler is the person who taught me computer graphics, supervised my master’s thesis (the foundations for 3D Tiles), encouraged me to author 3D Engine Design for Virtual Globes (a precursor to CesiumJS), and to teach graduate-level GPU programming at a time when these things seemed far beyond my capability. As I and several other members of the Cesium team who studied computer science at Penn can attest, he has a knack for making graphics seem easy while also pushing the limits.

Professor Badler recently retired after 5 decades of teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was most recently the Rachleff Family Professor in the Department of Computer and Information Science.

Dr. Norm Badler with Patrick Cozzi and other Penn computer science students, faculty, and families in 2008.

Professor Badler was 17 years old in 1965 when he first learned to program on an IBM 1620. By the 1970s, he was in graduate school at the University of Toronto. It was the famous mathematician H.S.M Coxeter who encouraged him to pursue computer science, believing that, “computers can be useful to mathematicians.”

After finishing his Masters in math and fueled by a dream of doing AI on computer understanding of images, Professor Badler completed his PhD in computer science in 1975. A year earlier he began teaching at the University of Pennsylvania.

Working at the intersection of math, geometry, AI, interactive systems, computer vision, and art, Professor Badler received over $30M in grant and contract funding which supported a vast number of PhD students. He is widely recognized as the pioneer behind computer graphics research at Penn from the 1970s until today, and has held many roles in the department, including Chair and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs for Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science.

In the mid-90s, he was CEO, CTO, and CFO of a small business inside the University, producing the Jack software for interactive ergonomic human models and simulation, a solution that still exists today as an interactive human model marketed by Siemens.

Professor Badler was the founding director of the University’s Center for Digital Visualization (the ViDi Center), the Center for Computer Graphics, and the Center for Human Modeling and Simulation. He is also credited with building the Digital Media Design Undergraduate Degree program and (together with Prof. Stephen Lane) the Computer Graphics and Game Technology Masters program, both in Penn Engineering. Combined, the programs have over 600 alumni.

While at Penn, he also became involved in ACM SIGGRAPH, an organization he would grow exponentially and serve as member of the executive committee as well as Vice-Chair. In 2021, Dr. Badler was named to ACM SIGGRAPH’s Academy Class, considered one of the highest honors in the field of computer graphics.

I recently sat down with Norm, as he is known to me, to ask him some questions about his career, his thoughts on joining Cesium, and the challenges posed by the metaverse.

PJC: What sort of goals and tangible products have motivated you over your career?

NB:Let me answer that in two ways. First, I’ve always been motivated by the idea of using computers to emulate human understanding of the world. Second, the tangible products of research are publications, grants and contracts, software products, and peer acknowledgments (talks, visitors, etc.). Yes, I have all of these, but the most tangible and rewarding “product” of all has been the students that passed through my life. I am endlessly grateful to them for defining new concepts, approaches, and artifacts. Every one of my PhD students has been an intellectual multiplier, taking me well beyond my knowledge or comfort zone. And the occasional Masters student like you, who went beyond coursework to do a Masters Thesis fits well into this category, too.

PJC: You have been involved in computer graphics since its start, what has remained the same and what has changed?

NB: Let me start by co-opting the metaphorical wisdom of others (I no longer recall its source): research is like working to expand the radius of a balloon by adding to knowledge on its surface. When the balloon is small, an individual’s contribution - in terms of surface area - increases the radius appreciably. As the balloon expands, that same amount of surface contribution contributes less and less to the radius growth. Or, equivalently, the amount of work needed to enlarge the balloon increases exponentially.

The point here is that I (and others, of course) were extremely lucky to be involved in computer graphics when its “balloon” of intellectual content was still small. The entire CG field itself traces its origins to Ivan Sutherland’s pioneering work on “SketchPad” in 1963. My first efforts at CG were in 1968. There were lots of places on that balloon surface to make significant (or even trivial!) contributions to the expansion of the field. Even an individual could appreciably increase that radius “way back then”. Such increases were evident in the mathematics and physics of modeling, rendering, and animating objects, materials, and creatures.

Today, it is much more difficult to expand that CG balloon. PhD students strive for technical advances and results that reward them with SIGGRAPH papers, peer recognition, and interesting careers. Papers have multiple authors. Industries such as games and movie effects fund (internal) algorithmic work as well as high quality output. So does that mean it is hopeless (or exceedingly difficult) to make contributions to CG? NO! The flaw is in the metaphor: the balloon is not a single sphere! It is in fact more like a fractal, with a very “bumpy” surface and protuberances that give it novel shape and effectively infinite surface area. Making a contribution to “bud off” a new bump, or expand an existing one, or even merge two different “area” balloons along a common seam is the way things are done now.

Another way to look at that last point is to see computer graphics as the greatest vehicle (beyond mere mathematics) for integrating disparate fields. Indeed, CG is now crucial in visualization of virtually anything, real or imagined. Even more fundamentally, CG is contributing to and itself being enhanced by advances in AI, machine learning, and computer vision. There is no doubt that as a vehicle for expressing and enhancing artistic creativity, CG is (arguably) the most effective medium of all. (OK, maybe music can exist without CG, but features such as score production, mixing, and sound visualization still use graphics.)

Well-known intellects call Physics the “King” of the sciences and Mathematics the “Queen”. Allow me the conceit of terming Computer Graphics the “Jack” [of all trades].

So the bottom line is that if you want to do great CG now, learn or do something else well, too!

PJC: You have known Cesium since our start; how has your view on the use of 3D geospatial changed over time?

NB: I think I remember telling you how brave you were to tackle problems seemingly addressed by the tech behemoth Google in their Earth app. But you convinced me that I was wrong when you published your book. It seems now that providing an open source, integratable, geospatial platform is a stroke of brilliance.

PJC: What are the biggest unsolved challenges in the metaverse?

NB: I’ve been influenced by Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash idea of the Metaverse: a seamlessly integrated large scale virtual experience with interacting avatars. (Jan Allbeck and I did a published analysis of the Snow Crash avatars.) I’ve spent a good chunk of my research years on virtual humans, and thought less about situating them in a world-size space. It does intrigue me to imagine real-time information feeds updating a metaverse experience. Time is multi-scale, and a metaverse that can support fine time scales and readily merge real-time information feeds has to be one major challenge. I envision, for example, real-time traffic (which seems imminently doable now) and simulated crowds (based on sensed density, which also protects individual privacy). I believe there are real user and economic drivers for such technology. Similarly, expanding timelines backwards into historic data, places, and events is presently a painful one-at-a-time process. I hope we can see the data origination problem addressed in near future efforts.

True to our values, we are making this move into metaverse research with collaboration at the forefront. We believe that innovation happens at the intersection of fields and the intersection of organizations.

We are interested in working with industry and academia partners to benefit the community. Get in touch with Professor Badler, norm@cesium.com, to explore collaborating with us on advancing the open metaverse at the intersection of the physical and the digital.